On one level or another, we all yearn for alternate histories.

Is there anyone who doesn’t wish they could redo something in their past? Not utter a cruel remark which destroyed a friendship? Not hurry through the last time you spoke with a loved one? Take the road never taken or the risk never risked?

To say nothing of the worst histories we share. Of world wars and slavery and genocides and hate and environmental destruction and so much more. If these events could be undone, wouldn’t the world we live in today be so much better? Or would righting historic wrongs result in even worse outcomes today?

Such questions are impossible to answer, except through the imaginative visions of alternate histories.

In my personal history I learned my love of science fiction from my grandfather, whose collection of Golden Age SF magazines and books fired my imagination. I also learned of my desire for alternate histories when my grandfather died when I was only 13.

I remember walking into his bedroom after his death to discover the last SF book he’d been reading, a paperback anthology of classic SF stories. A dog-eared page halfway through the book marked where my grandfather stopped mid-story, planning to return to the book when that day was over.

Instead, a heart attack killed him as he raked leaves.

I still have the dog-eared paperback as he left it, paused between the reading of one sentence and the next.

In an alternate timeline where my grandfather lived, I wonder about the conversations we’d have shared on science fiction and life. Would he have liked reading my SF stories? Would we have savored our extra days together or would we have impatiently frittered it away as humans usually do with our time?

Ironically, the last book my grandfather read was edited by Poul Anderson, one of our genre’s early authors of alternate histories. Anderson’s Time Patrol stories, where valiant time travelers ensure history stays on its “correct” timeline, are an integral and fun part of SF’s long tradition of time travel fiction focused on keeping history pure. He also wrote a famous series of alternate history fantasies called Operation Chaos, originally published by The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in the 1950s. In these stories World War II was fought between completely different countries with magical creatures such as werewolves and witches.

Of course, Anderson’s stories of time travelers keeping the timeline pure and correct seem a little simplistic today, just as historical narratives today are far more complex than they were decades ago. I think this is partly because most historians now recognize how imprecisely history is recorded. History as it is written can even be called the original version of the alternate history genre, where the story we're told deviates from what really happened.

After all, history is written by the victors, as the cliche states. Which means much of what happened in the past is left out or altered before history is recorded. And even the victors don’t name all the victors and don’t celebrate all their victories and deeds.

Theodore Sturgeon famously said that "ninety percent of everything is crap.” This applies equally to history as we know it — including the history of the alternate history genre.

I say this last part because this is the point in my essay where I’m supposed to give examples of classic works of alternate history, and how these stories influenced everything that followed.

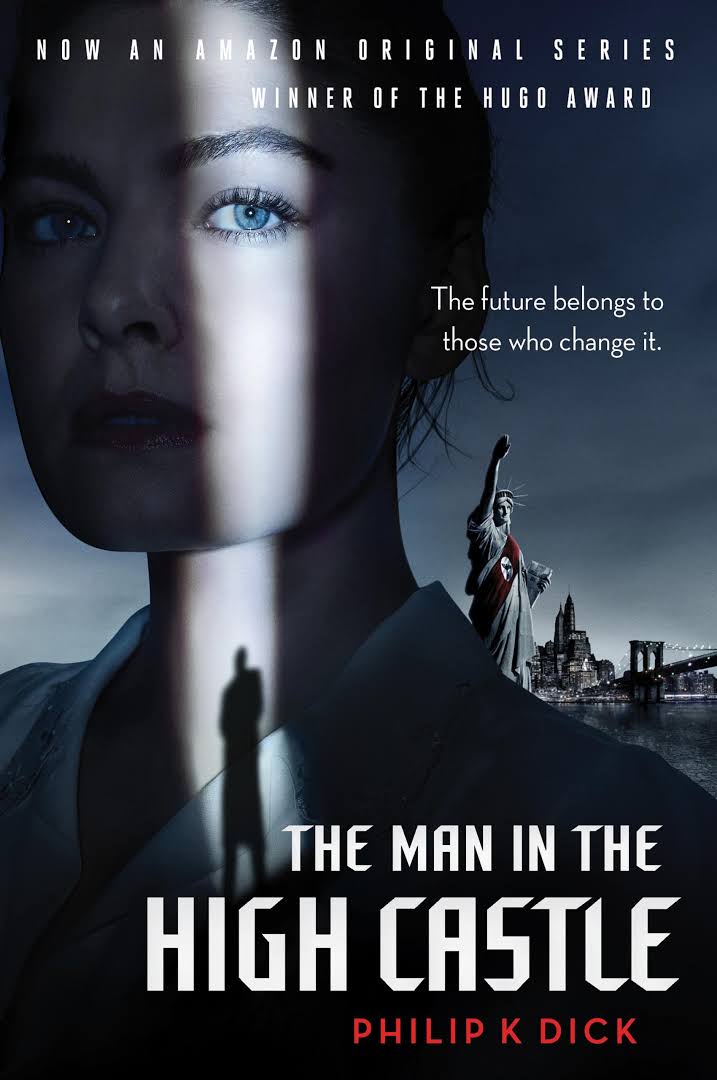

For example, Philip K. Dick’s novel The Man in the High Castle, in which the Axis Powers won World War II, is everyone’s go-to title when discussing alternate histories. And for good reason. While The Man in the High Castle isn’t the first true alternative history exploring completely different timelines from our own, the novel was the first to make a major splash in the SF/F genre, winning the Hugo Award and inspiring generations of storytellers.

Another famous alternate history novel is 1990’s The Difference Engine by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, which almost single-handedly sparked the subgenre of steampunk. As with Dick’s novel, The Difference Engine truly rewrote the history of our genre, with everything that followed being completely different.

But while the importance of these two novels can’t be ignored in the history of alternate histories, there’s much more to the history of this exciting genre. Authors like Poul Anderson, Andre Norton, Fritz Lieber and so many others wrote stories which helped establish the alternative history genre, yet their genre-defining works are only mentioned in passing these days.

Another example of an author whose alternate histories don’t receive enough credit for creating the genre is Harry Harrison. His alternate history novel West of Eden and its sequels opened my eyes to the full-scale revolution which could be wrought by changes in humanity’s timeline. In Harrison’s narrative of history Earth wasn’t struck by an asteroid 65 million years ago, allowing the dinosaurs to not only survive but to evolve intelligence and create a civilization which has lasted for millions of years, with humanity emerging in their shadow.

To me, West of Eden and the novel’s sequels contain the full power of what alternative history could and should be. But that’s merely my view. After all, everyone’s view of history is different.

What is certain, though, is that we are living in boom times for alternate histories. Must read works in the genre include many of the novels of Harry Turtledove (dubbed “the master of alternative history” for works in which the Confederacy wins the American Civil War, or aliens invade Earth during World War II). Other great works include Michael Chabon’s Hugo and Nebula Award winning The Yiddish Policemen's Union, about Jewish refugees founding their own city in Alaska; A Stranger in Olondria by Sofia Samatar, a poetic tale which skirts the boundaries between pure fantasy and alternative history; Eric Flint's 1632 series, about a small town in West Virginia transported to 17th century Europe; and Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell by Susanna Clarke, which creates an England existing solely through the grace of magic.

And that short list doesn't even begin to count all the non-Western alternate history stories like Musubi no Yama Hiroku by Ryō Hanmura, which reworks centuries of Japanese history. I've long wanted to read Musubi no Yama Hiroku but the novel has yet to be translated into English.

I think alternative histories will always be with us for the simple reason that humans can’t stop thinking about alternatives to the lives we lead. We yearn to know what could have been. Of the roads not traveled, be they good or bad.

With alternate histories, even history itself isn’t a barrier to our imaginations.